Introduction

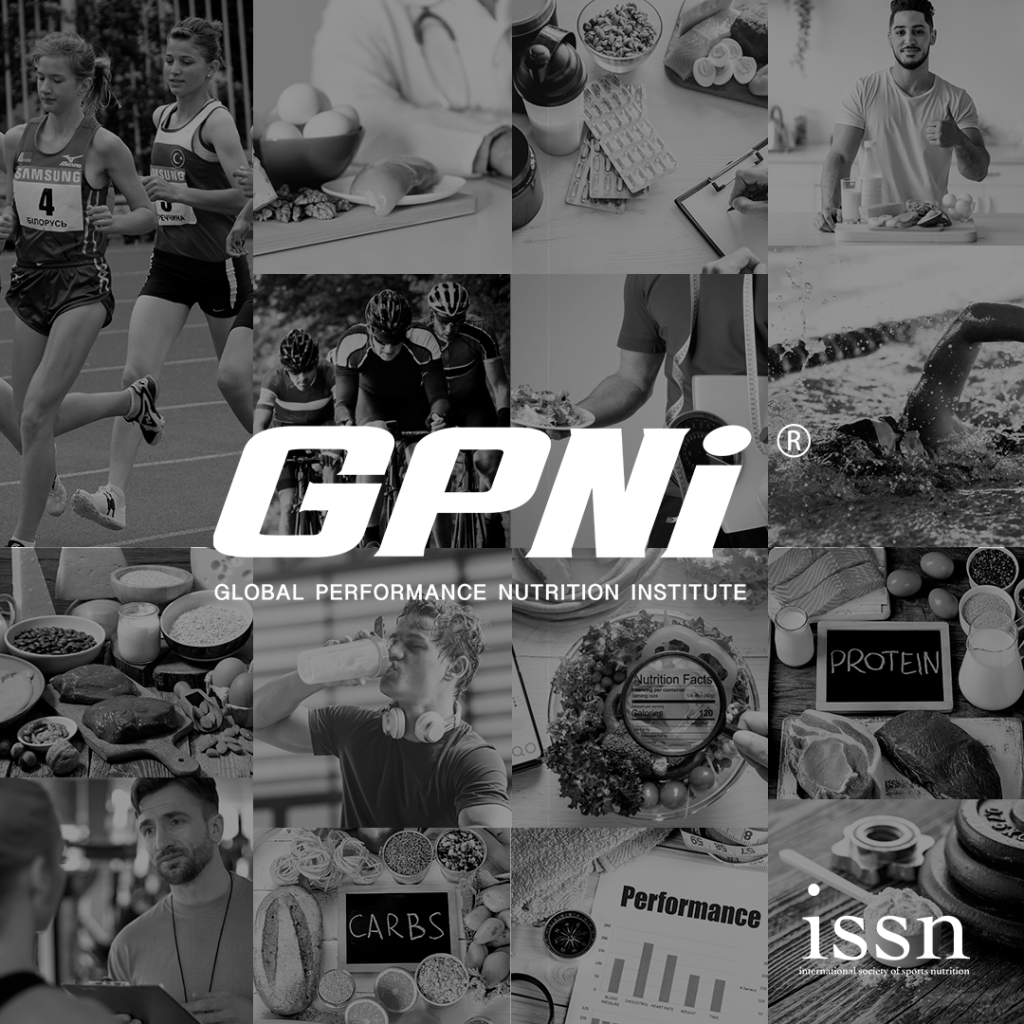

Water and hydration is an enormous part of our existence, however, that it is often taken for granted. It has proven to be a brilliant performance enhancer. Unfortunately, many athletes tend to overlook the power of this necessary element. When we disregard our body’s great need for proper hydration, everything is at risk.

What is Hydration?

Hydration has to do with the body’s total water volume. It is an aspect of fluid regulation that involves the homeostatic regulation, composition, and distribution of total body fluid volume. Inadequate water in the system will cause dehydration which can be mild or fatal depending on several factors.

Mild dehydration may cause dizziness, headache, flushed skin, and of course, reduced physical performance. In this case, the dehydrated athlete will be unable to exert energy and certainly has no endurance for energetic sports of any kind. Extreme dehydration is even more problematic, able to cause difficulty, poor blood circulation, and increased body temperatures in some cases. Some researchers suspect it may contribute to urinary tract infections and kidney stones formation.

Proper hydration will prevent weakness and even reduce the oxidative stress that characterizes high-intensity exercise as found in endurance sports. What’s more, some studies have shown that drinking water can help relieve headaches in those who experience frequent headaches.

The best hydration status occurs when the amount of water or fluid taken in, is enough to make up for water being lost. If water input is insufficient, this results in hypohydration. Hypohydration is dangerous and can lead to hyperglycemia, cardiovascular diseases, and urinary system diseases. Studies have shown that hypohydration even impedes physical performances, cognitive performances, and a person’s mood.

Interestingly, water is not the only thing that helps in hydration. All fluids count as well as foods with high water content. Tomato is 95% water while watermelon is over 92% water. Other foods like cucumbers, celery, grapefruit, strawberries, watercress, and radishes are equally hydrating. Low-fat milk is about 90% water, coffee is at around 99% water.

Research on the effect of three different hydration drinks (water, W; Gatorade, CHO-E; and low-fat skim chocolate milk, CHC) on three adults, post-exercise, using their urine samples revealed that rehydration occurred in all drinks after exercise. And that the use of chocolate milk which is a nutrient-dense drink may even be a more attainable way of reducing urine output, thereby retaining more water in the body. The result is that an athlete can have a more euhydrated state after exercise.

On the other hand, salty foods or meals that are high in sodium are dehydrating because the salt is absorbed and circulated throughout the body, so the body responds by extracting water from the cells to create balance, thus causing more thirst.

To boost your water intake, you could add some pieces of fruits into your water, for instance, lime or grapes; have a customized water bottle to serve as a visual reminder to drink up; set goals for yourself; and have a glass of water after meals. All of these and more will improve hydration.

On the Safety of Beta-alanine

Some myths and exaggerations have been formed about hydration and dehydration. One is that, if you feel thirsty, that is a sign that you’re already dehydrated. While this is a helpful reminder for people to pay attention to the signals sent through the system, there are still a lot of things that can make a person feel thirsty asides from dehydration. A clear sign of dehydration is the color of urine. If the urine is dark yellow, then you’re likely dehydrated.

Current best practice for assessing hydration level involves isotope dilution to measure total body water; osmolality of blood, saliva, or urine; colour of urine; and changes in body mass. However, because these techniques are either too expensive, intrusive, or require clinical laboratory equipment (amongst other reasons), a new way of assessment was developed.

The latest scientific research reveals that intraocular pressure/IOP (pressure within the eye) can be used to assess dehydration. It is faster, has accurate measurement and can be done by anyone with basic training.

The study proposes that IOP is impacted by hydration status, possibly because of a rise in blood osmolality on the rate of formation of aqueous humour. For the best result in assessing hydration status, use a combination of techniques as each have corresponding strengths for better accuracy.

https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-020-00381-6

Another popular myth is that you should drink water as much as possible to avoid dehydration. Drinking too much water can lead to a condition known as Hyponatremia. This happens when the concentration of the sodium electrolyte gets too low, causing swelling in the cells and possible harm to the body.

Exertional Hyponatremia (EHN) is a potential medical emergency for athletes during exercise. When overhydration dilutes the blood, an osmotic pressure ascent causes water to move into cells. The resulting cell swelling can result in EHN, one of the few illnesses that are potentially fatal to otherwise healthy athletes during exercise.

Recognizable symptoms appear in most athletes at a specific serum concentration and include lightheadedness, dizziness, nausea, puffiness on the hands and feet, and body weight gain. Severe symptoms of hypernatremia may include headache, vomiting, frothy sputum, difficulty breathing, pulmonary edema (i.e., fluid accumulation with swelling), and altered mental status such as confusion or seizure that results from cerebral edema. You must seek medical attention as soon as you notice these symptoms.

A study investigated the prevalence of Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia (EAH) and found a high occurrence in ultra-running. This emphasizes the need for a deliberate hydration strategy when participating in endurance activities. There was a high incidence of Hyponatremia in hot temperatures, but less so in moderate temperatures. It was also noticed that NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are commonly used by athletes competing in endurance sporting events. These drugs are a risk factor for hyponatremia and altered renal function.

Effects of dehydration on Athlete’s performances

During exercise, dehydration occurs to varying levels of hypohydration and fail to regain the mass depletion immediately after the exercise despite intake of fluids during and after exercise. This situation has been referred to as both voluntary and involuntary dehydration.

On athletes, the effect of dehydration is much more noticeable. Mild dehydration of 1–3% can weaken energy levels, impair mood, and lead to major reductions in memory and brain performance. Research has found that fluid loss of 1.6% was harmful to working memory and increased feelings of anxiety and fatigue in young men. This loss can easily occur through normal daily activities, let alone during exercise or high heat.

The body produces 8 to 16 ounces (250 to 500 milliliters) of water per day during normal metabolic processes. For an athlete, it is even more. During a marathon, a runner’s muscles can produce that amount of water in about two to three hours. When muscles burn glycogen, they simultaneously release about 2.5 units of water for every 1 unit of muscle glycogen; this helps protect against dehydration. Water and salt losses in sweat have implications for the health of athletes who exercise in hot environments. Water and sodium deficits are recognized as predisposing factors for exertional heat stroke, heat cramps, and heat exhaustion.

If you are a 150-pound athlete, you’ll start to feel thirsty once you’ve lost about 1.5 to 3 pounds of sweat (1 – 2% of your body weight). And you are seriously dehydrated when you have lost 5% of your body weight.

An athlete can lose as much as 6–10% of their water weight in sweating. This loss will lead to increased fatigue, altered body temperature, and general difficulty in exercise both physical and mental. The brain is strongly affected by your hydration status so stay hydrated and be at your absolute best.

Needless to say, that dehydration can hinder athletic performance. Athletes who lose more than 2 percent of their body weight lose their mental edge and ability to perform optimally in hot weather.

However, 2-5% dehydration does not seem to hinder strength or performance during short intense bouts of anaerobic exercises, for instance, weightlifting. But distance runners slow their pace by 2% for each percent of body weight lost through dehydration. Sweat loss of more than 10 percent body weight can be life-threatening.

Clarification of terms

- Euhydration: This is when an individual has a normal body water content.

- Hypohydration: When an individual has lower than normal content.

-

Dehydration: The process of losing body water

Conclusion

On a normal day, thirst prompts consumption of water and is measured at a subjective rate. During inactive daily activities, the perception of thirst, the act of drinking, renal regulation of water, and electrolytes adequately regulate total body water volume from day to day. But during prolonged endurance exercise, the relationship between perception of thirst and whole-body fluid-electrolyte balance can be usurped by physiological challenges such as major loss of water and sodium in sweat. Therefore it is important to maintain the right water levels by intentional hydration as an athlete.

GPNi® Endurance & Marathon Nutrition Coach EMNC®

To learn a great deal more about the importance of hydration during endurance events, please investigate learning more about the Endurance & Marathon Nutrition Coach (EMNC®) certificate program. Deep dive on all the strategies involved in training, pre competition and post competition recovery, as well as the safety to be taken into consideration. Based on the very latest scientific research by the ISSN®, other institutes as well as exclusive research by Dr. Jason Lee who has spent the last 20years researching sports nutrition related to endurance events.

For those that are already certified with the Sports Nutrition Specialist (SNS®) international certification, receive 4.5 CEC points when attending this online certificate program.

For more information, please get into contact us or learn more on the page.

REFERENCES

1. Cheuvront S.N., Kenefick R.W. Am I drinking enough? Yes, no, and maybe. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016;35:185–192.

2. Greenleaf J.E. Problem: thirst, drinking behavior, and involuntary dehydration. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992;24:645–656.

3. Barnes K.A., Anderson M.L., Stofan J.R., Dalrymple K.J., Reimel A.J., Roberts T.J., Randell R.K., Ungaro C.T., Baker L.B. Normative data for sweating rate, sweat sodium concentration, and sweat sodium loss in athletes: An update and analysis by sport. J. Sports Sci. 2019;37:2356–2366.

4. Sawka M.N., Burke L.M., Eichner E.R., Maughan R.J., Montain S.J., Stachenfeld N.S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007;39:377–390.

5. Noakes T.D., Sharwood K., Speedy D., Hew T., Reid S., Dugas J., Almond C., Wharam P., Weschler L. Three independent biological mechanisms cause exercise-associated hyponatremia: Evidence from 2135 weighed competitive athletic performances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18550–18555.

6. Kerksick, C.M., Wilborn, C.D., Roberts, M.D. et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 15, 38 (2018).

Online References

https://www.everydayhealth.com/dehydration/the-truth-about-hydration-myths-and-facts/

https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/7-health-benefits-of-water

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908954/

https://www.teamusa.org/USA-Triathlon/News/Blogs/Fuel-Station/2013/November/25/15-Hydration-Facts-for-Athletes

https://www.precisionhydration.com/science-of-hydration/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15212747/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15212747/

https://extremephysiolmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2046-7648-4-S1-A139

https://mmrjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40779-021-00327-2

https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-020-00381-6